Against Stigma, Mercy

Rembrandt, Kant, and everyday compassion as the foundation of the doctor-patient relationship

We are flawed. Except in cases of mental conditions that distort self-perception, we all recognize this premise.

Illness is often not a fortuitous event but the result of a complex interaction between genetic, biochemical, and behavioral factors. Smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, and inadequate diet are risk factors that can lead to a series of diseases which, because they are neither self-limiting nor curable in the strict sense, are deemed chronic.

These chronic diseases carry with them, in varying shades and intensities, many social stigmas and prejudices. Even in the face of the evident interaction of genetic, biochemical, and behavioral factors in the origin of these conditions, it is the behavioral factor that most reverberates in patient care. Stigmas echo, and the notion that we are all fallible falls silent.

Stigmas arise from moralistic views, lack of specific educational training, emotional exhaustion, and cultural and social stereotypes. This stigmatizing bias blames the patient for their condition instead of recognizing dependency—whether on food, alcohol, or drugs—as a chronic, multifactorial disease.

Such stigmatizing segregation, today more subtle and veiled, contrasts with the explicit forms of exclusion seen in the past, when the marginalization of patients was physical and institutionalized. A striking literary example of this practice is the novel The Magic Mountain, by Thomas Mann, set in the Berghof sanatorium in Davos, at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. As I analyzed in How Illness Dehumanizes the Body, an atmosphere of institutional coldness predominates, with rare manifestations of compassion or mercy. Care exists, but it is cold and technicist — only nature’s mercy remains, the merciful narcotic of illness itself, to ease the suffering.

Stigma is often unconscious and may result in therapeutic limitations, cloaked in seemingly technical decisions such as “lack of social support” or “low expected adherence.” The projection of this stigma results from the fading of empathy and mercy.

The ability to understand another’s feelings, to perceive their perspectives, to place oneself in their position, is the definition of empathy. To act with kindness and clemency based on empathy, seeking to alleviate pain or offer a new chance when one has the power to punish or judge, is the definition of mercy.

In the treatment of illnesses with behavioral components, there is broad recognition of a moment—or set of critical moments—when the patient experiences a significant change in trajectory, whether in motivation, self-perception, or treatment engagement. This turning point, this epiphany—often following a “rock bottom” experience—is commonly associated by patients with an empathetic gesture from another person, resonating with the idea of mercy.

The merciful act is an act of restoring human dignity, for the patient, when desacralized, is dehumanized—and as a society, we decline morally. Saint John Paul II, in his encyclical Dives in Misericordia (1980), teaches that “mercy should be understood and practiced unilaterally, as a good done unto others.” By offering mercy, we offer patients the possibility of a “turning point,” where they feel welcomed, with the chance to rebuild self-esteem and engage in recovery. Still in the pope's words: “the one who is the object of mercy does not feel humiliated, but somehow rediscovered and revalued.”

In a therapeutic context, mercy is powerful. Being merciful does not mean ignoring harmful behaviors or allowing manipulation by the patient. It aligns with the imposition of clear boundaries and accountability on the path to recovery.

When conveying the importance of the “turning point” in chronic diseases with behavioral components—as recognized in psychosocial and cognitive-behavioral approaches—and associating it with the concept of mercy, particularly by using the words of a saint, I consciously run two risks.

The first is that acting with mercy may seem Herculean to healthcare professionals, within reach only of very exceptional individuals, almost saints, or something that must be accompanied by pomp and grandeur.

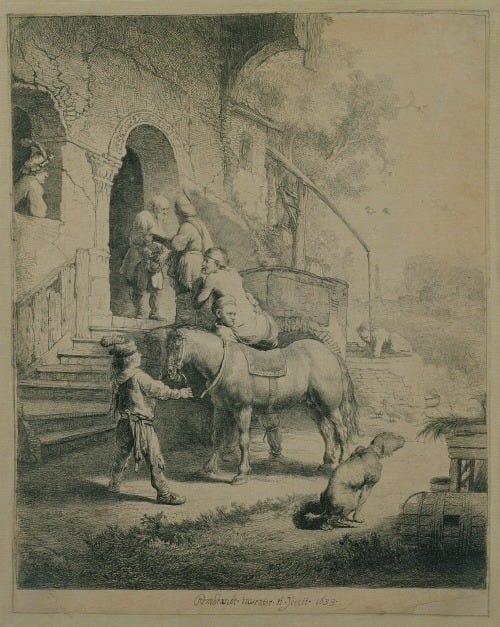

I believe I can refute this first risk by using the visual narrative of a work of art: The Good Samaritan, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), exhibited at The Wallace Collection in London.

This image is an etching and burin engraving. Rembrandt conveys a remarkable sense of volume, atmosphere, and movement. First, he would draw on a metal plate covered with varnish, exposing the metal with a needle. The plate was then dipped in acid, which corroded the drawn lines (etching). Afterwards, he used the burin, a carving tool, to reinforce or deepen details, creating contrast and texture.

The Renaissance engraving depicts the Good Samaritan, devoid of pomp, a common man delivering the wounded to the innkeeper. But Rembrandt’s expressiveness and humanity erupt in another detail — the dog defecating — a reminder that compassion is devoid of glory. Mercy, then, is something “impure” yet necessary and ethical. It is “impure” because it does not require spiritual elevation. Being merciful demands no glory or spotlight. It is within everyone's reach. It is unilateral. It is necessary.

The Good Samaritan’s merciful act is not performed by a “special” person and does not necessarily require great effort. In the healthcare routine, the words and actions of all professionals—especially nurses, nurse technicians, and chaplains—who maintain a unique proximity to the patient and are capable of recognizing their humanity without judgment, can promote transformative “turning points.”

The second risk assumed, and perhaps the most challenging, is that a solely religious perception of mercy, seen as a reflection of divine love, may overshadow an ethical and humanistic stance. This perception may be amplified in times of cultural, societal, and individual secularization, or in healthcare environments that falsely dichotomize science and transcendence.

I refer to secularization as, culturally and societally, the diminishing influence of religion on morality and education; and individually, the reduced role of religion in everyday life, decision-making, and personal identity. This process is neither uniform nor linear, but the shift from the medieval Christian world to modernity (Renaissance, Enlightenment, French Revolution) is the historical transformation in which values and practices ceased being subordinate to religion and came to be governed by secular, scientific, or rational logics.

In this way, if the process of secularization aims to govern practices and values through rationalist frameworks, I aim to refute the second risk—considering mercy as solely religious—by drawing on the teachings of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). Considered one of the greatest philosophers of all time, alongside Aristotle, Plato, and Nietzsche, Kant is the inspiration behind the moral philosophy of the “modern individual,” one detached from a transcendent order governing the world. Kant had the sensitivity to perceive, reflect upon, and ground the rationality of morality while the process of secularization was unfolding.

Kantian ethical flame is centered on the categorical imperative, which teaches us that we must act according to maxims that could be universalized (first imperative) and that treat human beings as ends in themselves, never as means (second imperative). According to these principles—contained in Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) and Critique of Practical Reason (1788)—moral actions do not depend on feelings or personal inclinations, but rather on duty derived from reason.

Treating all patients with empathy and mercy, regardless of their circumstances (attention to stigma!), is a maxim that can be universalized and thus aligns with the first categorical imperative. This reasoning directly resonates with the second formulation of the categorical imperative: it means recognizing the patient as an end in themselves—a being endowed with inherent dignity, independent of their behavior. These categorical imperatives have direct application in contemporary bioethics, reflected in principles such as beneficence (acting for the patient’s good) and non-maleficence (avoiding harm).

Although Kant subordinated emotions to reason, the introduction of empathy into the clinical context does not weaken moral duty—it enhances it. It humanizes the doctor-patient relationship, transforming it into more than a rational bond.

Returning to Rembrandt, mercy is something impure, but necessary and ethical. The healthcare professional may, according to their personal convictions, understand mercy as an expression of divine love—from a religious perspective—or as a gesture of compassion grounded in secular ethical principles. Or even, one may adopt a synthesis between these views. Regardless of the origin of this motivation, what matters is that mercy represents the recognition of the other’s humanity, free from moral judgment. It is a universal ethical principle. Therefore, the actions of the healthcare professional should not be based on feelings, stigma, or personal preferences, but on a constant moral commitment inherent in the doctor-patient relationship.

If we are imperfect, we must refrain from blaming others through stigma. We, healthcare professionals, by exercising empathy, cannot reproduce the social norm of stigmatizing these chronic diseases with behavioral components and morally exclude patients, turning our institutions into modern Berghofs. To exercise mercy—whether from a religious or secular perspective—can offer patients mechanisms — the space — for a “turning point” in their trajectory. This allows for the restoration of health, dignity, and autonomy. Let us remember: mercy is, at once, an ethical duty and an act of compassion.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese on July 05, 2025. You can read the original version here: