Between Syracuse and the Medical Chart

Archimedes, the palimpsest, and the medical art of writing to think

The creation of the practical alphabetic system by the Phoenicians (c. 1200 B.C.) had a lasting and structural impact on communication. Their system, easy to learn and replicate, served as the basis for the Greek alphabet, influenced Latin, and enabled the transition from oral to written knowledge. The technique changed history. The act of writing allows for new discoveries, reveals new ideas, and—above all—organizes our thoughts. This capacity for organization through writing enables us to reflect, free ourselves from chaotic cerebral thought, engage in creative thinking, and thus evolve. Our scientific evolution is a well-told story and a result of the power of the written word.

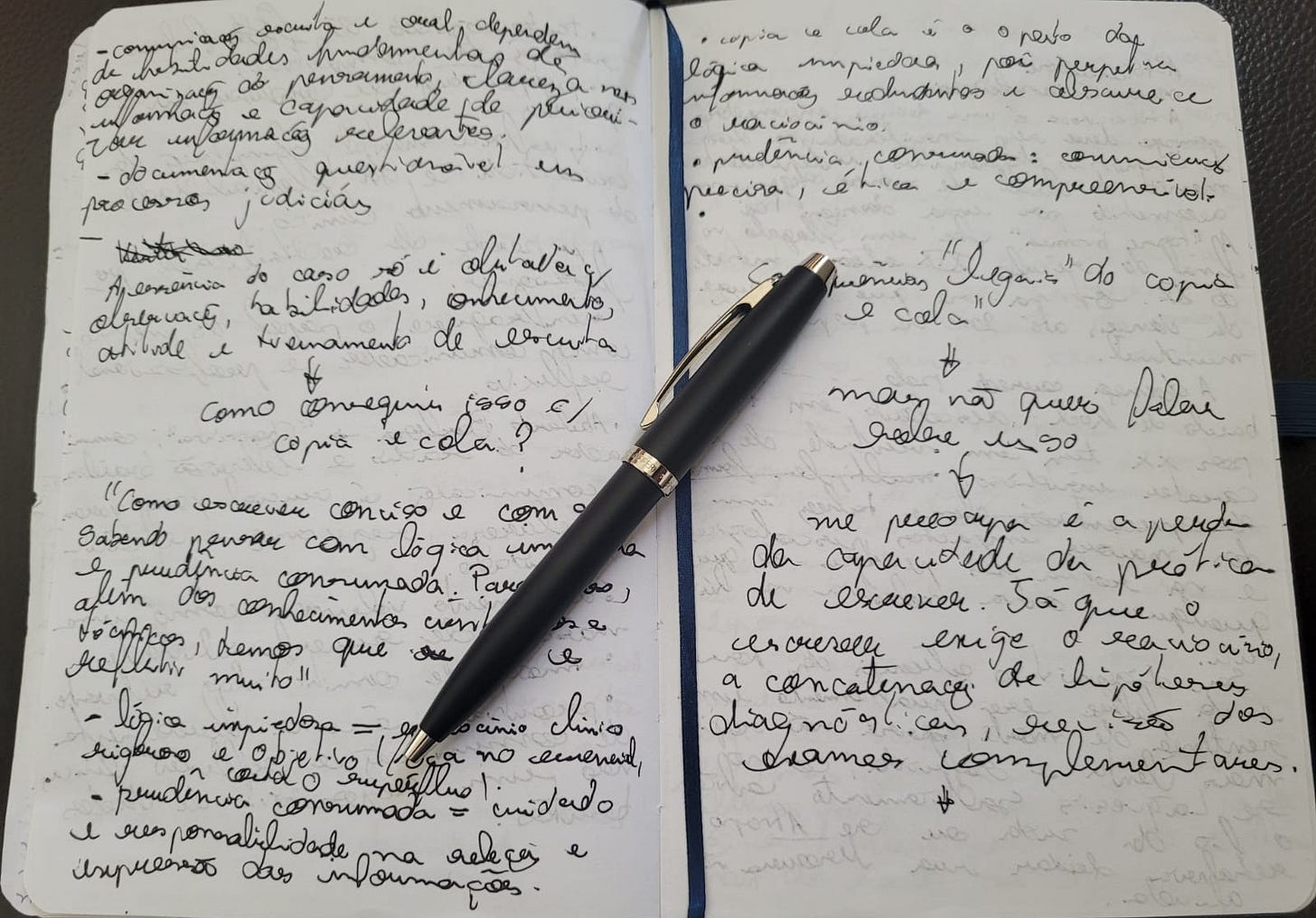

The physician must be a friend of the written word, for in the company of the medical chart lies the confessional of clinical practice, where one must describe the key points of therapy, the instituted clinical reasoning, including the nuances of challenges and specificities of the case. One should seek to develop the skill of organizing ideas, connecting clinical data, and justifying decisions—briefly and precisely. The medical chart is an essential part of care, not a bureaucratic task.

Writing, as a manual practice, activates broader neural connections than mechanical typing, promoting active attention, information retention, and cognitive elaboration. This allows writing to become something grander than a record: to articulate, organize, select, and decide. Medical writing has undergone a paradigm shift with the computerization of electronic medical records. In the era of handwritten charts, physicians were compelled—if only by time constraints—to develop the technique of clear and precise writing in clinical records (without delving into the merit of handwriting legibility!). Today, there is a widespread decline in the quality of records due to the “copy and paste” feature, which seems to be inducing a loss of the art of thinking with one’s hands.

Repetition without re-elaboration leads to a reduction in synthesis capacity, perpetuating irrelevant or outdated—if not incorrect—information, resulting in stagnation of clinical reasoning. This is not a senseless defense of handwritten records—for electronic systems offer countless advantages, such as legibility, remote access, and traceability—but rather a focus on the fact that mechanized content replication is generating bloated records, filled with narrative redundancy and lacking clinical focus. There is a clear confusion between quantity and quality of information.

This phenomenon reduces mental effort, limits creativity, and undermines the flexibility of clinical thought. Writing ceases to be the "reflection of ruthless logic and consummate prudence—fundamental characteristics of a concise and sensible chart," as João Manuel Cardoso Martins puts it. In current practice, electronic records—where previous notes are copied, a new detail is added, and rarely anything is deleted or reworked—result in multilayered, confusing, redundant texts, where clinical reasoning does not advance; it merely accumulates. We are not creating electronic records—we are creating digital palimpsests.

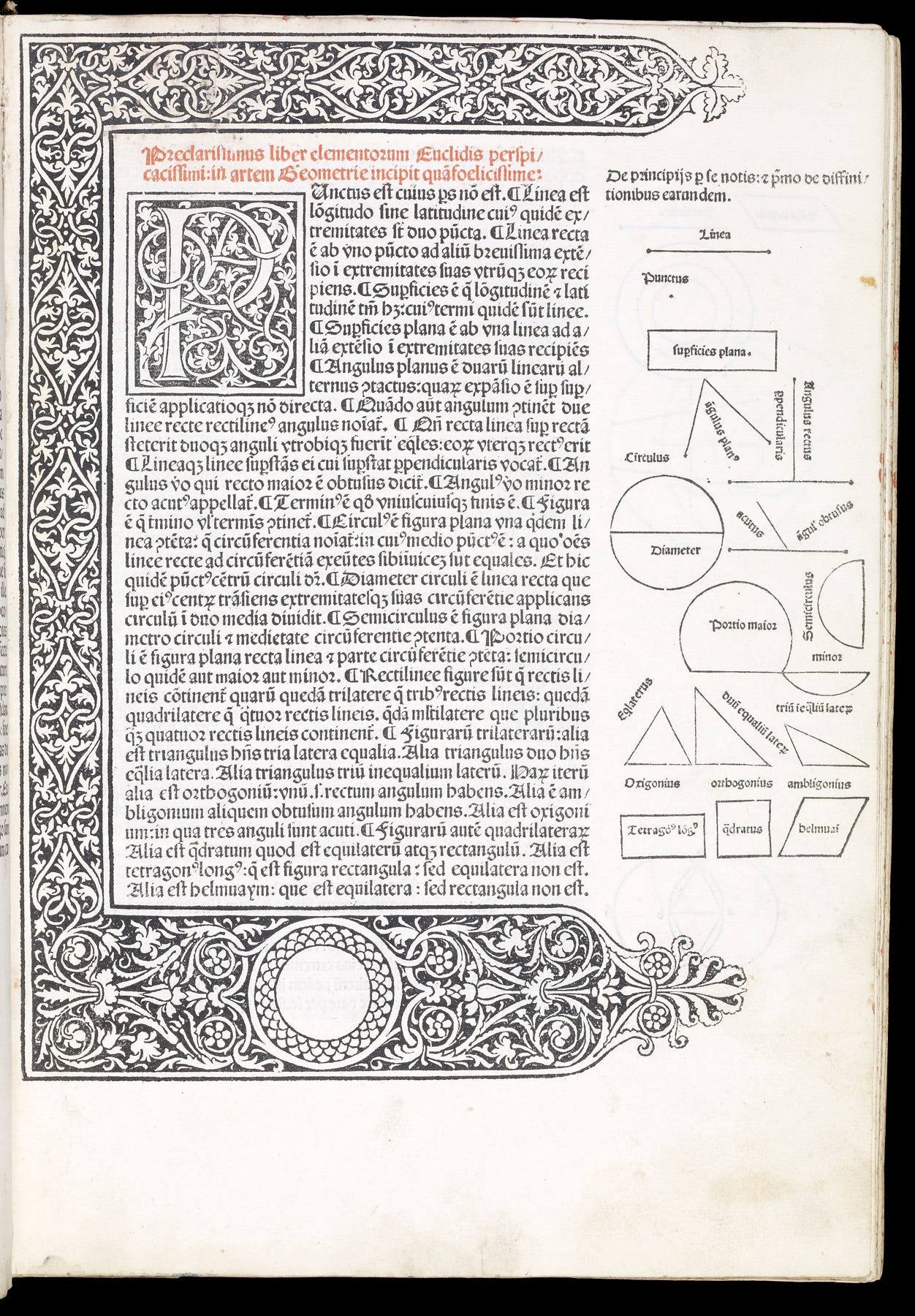

The term palimpsest comes from the Greek and means "scraped again" (palin = again; psēstos = scraped). In Antiquity and the Middle Ages, parchment was a scarce and expensive commodity, made through a complex artisanal process using animal skin, such as sheep or goats. There were manuscripts in which an original text was partially removed by scraping or washing, allowing the surface to be reused for new writing.

One of the most notable palimpsests in history is that of Archimedes, the Greek mathematician born in 287 B.C. in the city of Syracuse, located in Sicily, now part of Italy. Most of his life remains shrouded in obscurity. One iconic episode is his excitement upon discovering a mathematical principle while taking a bath, after which he reportedly ran naked through the streets of the city shouting the Greek word: “Eureka! Eureka!” He went beyond the his contemporaries, who merely listed their mathematical results—he wrote about how he arrived at them. His brilliance drew the attention of the Romans, and he was eventually killed by a soldier—apparently unintentionally—during the capture of Syracuse in 212 B.C. It is one of many historical examples of how ignorance can destroy genius.

It is believed that his work was compiled around 530 A.D. in Constantinople. Around the 10th century (c. 950 A.D.), a Greek scribe—also in Constantinople—hand-copied seven of Archimedes' treatises, including two that do not exist in any other known version. In the 12th century, the parchment containing these texts was scraped and reused by a monk, who wrote Christian prayers over them, creating the palimpsest. The manuscript was then bound as a prayer book and stored for centuries.

In 1906, the scholar Johan Ludvig Heiberg found the palimpsest in Constantinople (now Istanbul), photographed it in parts, and recognized fragments of lost texts by Archimedes. The book soon disappeared, entering the black market of art. It only resurfaced in 1998, when it was purchased at auction for two million dollars. The buyer handed it over for restoration and study to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Dr. William Noel, born in the UK and Ph.D. in Medieval Studies from the University of Cambridge, described that when he received the manuscript, a chill ran down his spine—he had never imagined that a material bearing witness to the mind of a genius dead for over 2,200 years would one day pass through his hands.

Between 1999 and 2008, Dr. Noel coordinated the project to recover the Archimedes Palimpsest, using multispectral imaging technology, ultraviolet light, and digital processing to recover the only known copy of fundamental works by the mathematician. These works revealed reasoning by the genius involving the equilibrium of forces and center of mass, geometric combinations, the value of Pi, and infinitesimal calculus. These findings confirmed that Archimedes' analytical reasoning was compatible with that of modern mathematicians and physicists.

We should recognize that the Archimedes Palimpsest represents a symbol of memory, traces of the past. In today’s clinical context, where we seek clarity and up-to-date information, the digital palimpsest holds multiple meaningless layers—merely remnants of unconsidered phrases. “Copy and paste” is not merely a technical issue, but also an ethical and cognitive one. Writing ceases to serve reasoning and begins to obscure it, resulting in the loss of professional credibility and the weakening of the physician’s role as a communicator and reflective professional.

In medicine, to write is to think, decide, and take responsibility. What is lost when writing becomes a mechanical function—a Sisyphean punishment—rather than an extension of clinical judgment? The electronic chart has become a modern palimpsest: it reuses the text, but erases the thought.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese on August 2, 2025. You can read the original version here:

To follow the incredible story of the unveiling of a genius's lost thoughts.

The Archimedes Palimpsest, erased by monks in the 12th century, resurfaced centuries later as a scientific treasure. Through cutting-edge technology, it was discovered that Archimedes already intuited concepts of calculus, geometry, and physics long before his time. Watch the documentary and follow the fascinating rescue of this work at the Walters Art Museum: