Is the spectator, and not life, the art really mirrors.

…

All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.

The Preface, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde, 1891.

The perfect writer would be an individual who renders himself — and his very essence — entirely and lucidly into words, employing an imperfect instrument, language, to produce perfection in the message. The highest ambition of every writer is to create a work, an aphorism, an idea that is axiomatic and cannot be altered, for it contains within itself the whole of its meaning, lacking neither excess nor deficiency, timeless and universal.

The fetish of the writer is to fail to see himself, leaving only a pair of transparent eyes fully disembodied. What remains is the perfect word, and the author dissolves into it. In truth, the perfect writer is a mathematician.

For mathematics is the desert of absolute exactness in language — universal, timeless. But here lies the dilemma: the closer we draw to mathematical absolute precision, in its linguistic equivalent, the further we stray from the floating, necessary richness of ambiguity — essential not to the transmission of pure information, but of sensations. A zero-sum equation. As Fernando Pessoa wrote: “Zero is the greatest metaphor. Infinity is the greatest simile. Existence the greatest symbol.”

Among metaphors, analogies, and symbols, perfect writing is the refined equation, resolved to its simplest possible solution. The initial equation and the final answer contain the same information, though at different levels of complexity, from the most intricate to the most simple. Yet, unlike mathematics, writing that is superfluous in order to convey the necessary is not complex — it is disastrous. It has nothing to do with the richness of ambiguity in words, concepts, or verses. In writing, true complexity lies in expressing thought with clarity. In poetry especially, emotion justifies the balance and play of words to express the multivalence of feelings, inexact by nature. The impasses of language mirror the ambiguity of subjectivity. Metaphors and analogies will never be perfectly grasped in their entirety; symbols express the existence of the hidden consciousness.

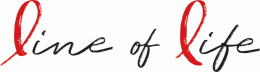

Like a perfect sphere, reflective and reflexive, without any deformities, excesses, or lacks, returning the image of the one who observes it — or reads it — yet transformed by its smooth, curved surface. It is the same observer, but altered by the sphere’s surface, or by the words of verse and prose. Here he may see himself, or imagine himself, in ways different from what he believes himself to be — and the more polished the sphere, the more skilled the writer.

Mediocre writers produce opaque surfaces.

I want verses like jewels that endure in the vastness of the future, as Ricardo Reis once said. A perfect sphere, language cut and polished like a diamond. And when reaching the summit of perfection, beyond the language that reflects the possible reader, transmuted by the essence of ideal and unreal prose or verse, to go further still and see through the reflective surface — the writer ceasing to exist, leaving only his essence transformed in his work. The perfect communion between writer and reader.

And yet, absolute coincidence between the two — in truth, between any two beings — is a mirage, for there is never total communication between entities that never fully reveal themselves, even to themselves. The writer dwells in a fissure, a space between what he wishes to express and the impossibility of saying everything. Yet, though he does so with the certainty of an unreachable result, he still writes, and the foretold, expected failure is illuminated. For there is no mirage without light, in darkness.

He tries, knowing that upon reaching where he hopes to arrive, he will find only aseptic dunes, the vast, relentless desert of meaning, mathematical. The rare oasis of understanding between one and another — even if terrible in the secrets it reveals — is literature.

This failure is literature, our unique and elegant way of facing the fundamental dilemma of language: being blind before subjective experience.

We only ever orbit full understanding, never landing, eternally drawn by the need to be recognized by the other.

We wish to be read, yet we can never be understood at our core. Writing always escapes its subject, even when it appears to capture or conquer it.

The flawed system of language exposes the impossibility of perfect communication.

But writing resists — or rather, it desires. It yearns to perpetuate itself, to carry itself through time, to conquer immortality. Because something is missing, because there is a void, we are always thirsty in the middle of the desert. We are symbolically governed by this need to fill that same void, that same lack.

As in love.

A painful truth, but also the driving force of creation: insatiability. Every writer is insatiable, the difference being that he knows himself to be so, and each word is a painful attempt to outwit impermanence. All writing, like love, is a failed act — the materialization of desire disguised, socially and morally acceptable.

All reading is a mirage.

But it is all we have. And it is the only thing we can possess. And yet — perhaps for that very reason — we persist in writing. I write in the space between two mirrors, one reflecting logic, the other reflecting desire. Philosophically, I seek the perfection of language, though I see the insurmountable fracture between self and other, for the desire of the other is never fully accessible. Aesthetically, we choose lyrical ambiguity as the force to reach where reason cannot.

But writing, even the purest, is translation.

A translation of oneself.

A plagiarism of oneself. For all translation is treason, because it is unattainable. From a being who seeks to demolish, word by word, his own consciousness in order to unveil his essence — attempting to recognize himself as human through the other. It is the subject exiled from himself; we can only feel the fragile surface of the other. He cannot be fully known, only evoked.

Writing is a kind of tragic offering, something that will never be entirely received.

The ideal reader is also a mirage; we write for no one. We invent worlds for people who do not exist. We give what we do not have to someone who is not.

We project a fantasy about what the other feels or understands, or about what we are to the other — as in love. A supposition of completeness. But it is all we have. And it is the only thing we can have.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese on August 16, 2025. You can read the original version here: