Writing and Freedom Share the Same Foundation: Danger

Courage is not an ornament, but a condition for relevance.

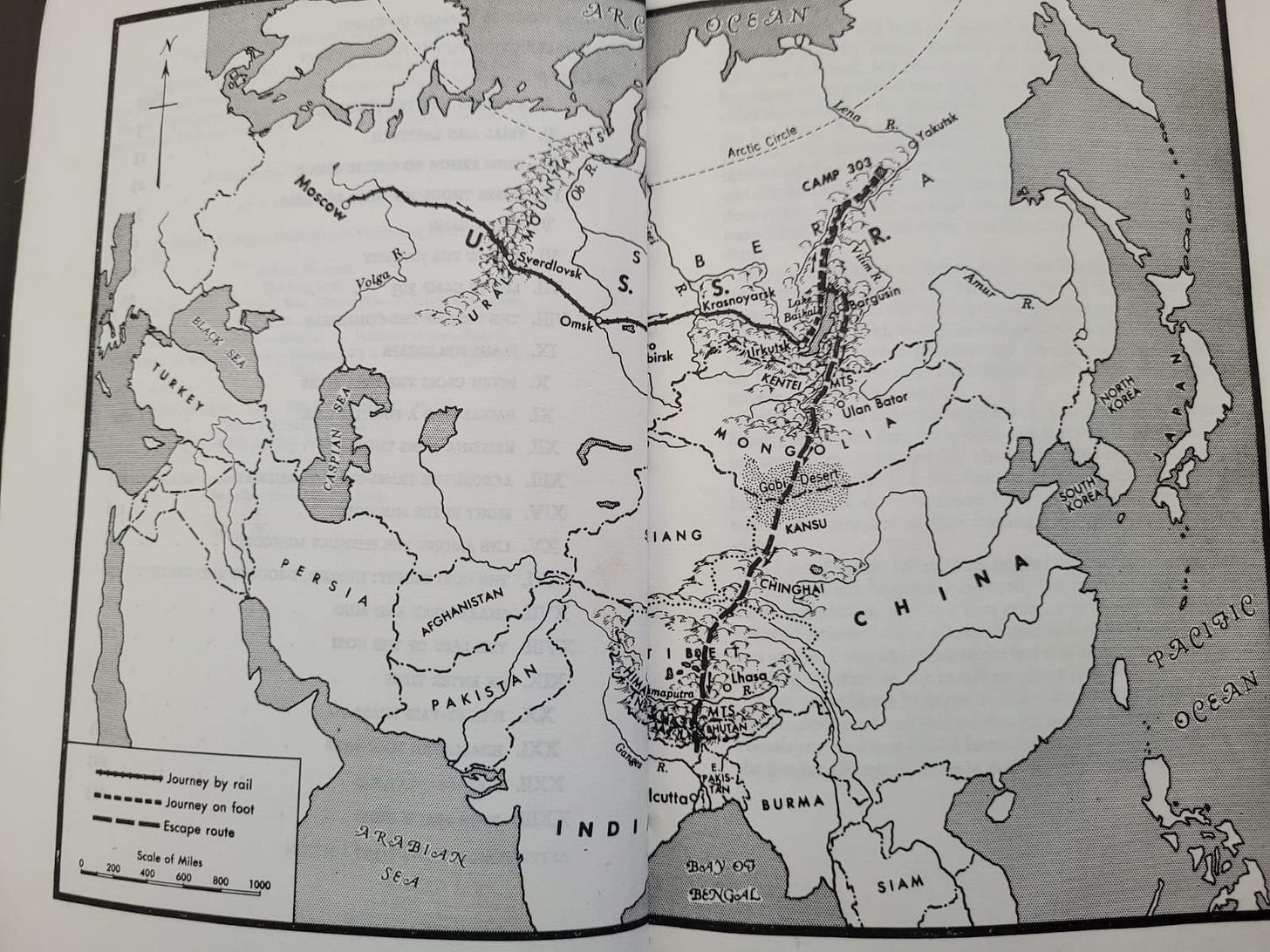

At the height of the terror of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the enemies of the regime were imprisoned in Siberia, where, isolated by geography and climate, they were subjected to forced labor and delivered to their grim fate. In 1941, Slavomir Rawicz, a Pole accused of espionage, together with a small group of prisoners, escaped from a forced labor camp and began a journey southward, crossing Siberia, the Gobi Desert, Tibet, and the Himalayas toward British India. The Long Walk, published in 1956, the result of a series of interviews the fugitive gave to Ronald Downing, is the epic account of this journey of courage in search of freedom.

We write because we want to convey something, information or emotions. At times, we are physician-writers or writer-physicians. In the first, we are allowed to choose between donning prêt-à-porter, haute couture, tailored, or creative clothing; in the latter, we wear the formal attire of the deontological duty (by the Code of Medical Ethics) to educate, promoting reflection and reforms. The crux is that disseminating medical science among physicians — in scientific articles, congresses — is easy; the problem is the transposition from reason to emotion, necessary for non-scientific dissemination. The cognitive tool of interpretation by the lay public is “a long journey that goes not only through logical and analytical reasoning, but mainly through impressions, a territory laden with emotions. Only the rational are convinced by rationality, naturally a small portion of the population. The majority must be reached by emotion, because they act emotionally all the time,” as João Manuel Cardoso Martins affirmed.

The first major goal of the fugitives was to cross the Lena River. Frozen solid, it stretched more than half a mile wide, still running thousands of kilometers to the Arctic Ocean. Overcoming this stage meant leaving the area of the forced labor camp and moving south, aiming to skirt Lake Baikal. Crossing this frozen geographical obstacle was a renewal of confidence, since “in all our minds had been the idea we might never reach the Lena.”

Written language is an imperfect instrument that never captures the full essence of the author or the reader. In The Perfect Writer, Ricardo Schulz reveals how the reader reflects altered in the sphere of writing and that the only way to achieve perfect writing would be to achieve mathematical precision, yet such precision would sacrifice the rich ambiguity of language, essential for conveying sensations and emotions. If Cardoso Martins shows the necessity of the transposition, Schulz teaches us where we must resolve this imbroglio: “The writer inhabits a fissure, a space between what he wishes to express and the impossibility of saying everything.” That fissure is Rawicz’s Lena River — wide, frozen, treacherous — the natural barrier similar to the imperfection of language that creates a division between the communicator (the rational physician) and the receiver (the emotional public).

Writing for human connection is a risk for the physician-writer, a source of danger, for medical themes are not only technical, but charged with explosive potential. Health deals with systems that aspire to perfection or equality but are undermined by inherent imperfections. In Against Stigma, Mercy, we touch upon emotional taboos of shame, vulnerability, and stigmas in mental health; in Faustão, Health and the Waiting List That Is the Same for Everyone, we reveal inequities in the transplant system — not by direct manipulation, but by socioeconomic disparities that affect patient preparedness and can impact trust in the system. In these texts, the danger for the communicator is palpable: by writing with transparency, one exposes oneself to accusations of elitism, reactions of skepticism, criticism from colleagues, and ethical sanctions. As “The Perfect Writer” warns, the ambiguity of language can be misinterpreted, as the public may see in medical revelations a mirror of their own social frustrations — the public becomes irritated by its altered reflection in the sphere of writing. This dynamic is not accidental; it is inherent, for medical themes deal with what is most primal: the fear of death, the hope of cure, and the indignation at injustices.

Reaching the Trans-Siberian Railway and arriving in Mongolia marked the transition from the Siberian winter to the more southern summer, in which heavy fur coats had to be abandoned during the day, though still necessary at night. There they found a good reception from the natives, who offered them nuts, dried fish, barley grains, and oat cakes the size of biscuits, all in equal portions among the members of the fugitive group, along with greetings and wishes of good fortune on the journey, courtesy, generosity, and hospitality. According to Rawicz, “the help received was according to the means of the giver, but that help was always cheerfully given.”

The crossing of the Gobi Desert is one of the most emblematic passages in The Long Walk. For days, the group walked under the scorching sun, without water, tormented by hallucinations and the death of two companions. To survive, they ate snakes and drank from muddy sources, which seemed like divine gifts amid the aridity. Rawicz recalls: “In the shadow of death we grew closer together than ever before. No man would admit to despair. No man spoke of fear.” Finally, they reached Tibet.

The transposition from rational to emotional is, in fact, the heart of the physician-writer’s craft, but it is not enough to recognize the transposition; it is necessary to accept the danger it brings: misunderstandings, criticism, accusations. To avoid exposure to danger, we may resort to three solutions: sculpting perfect, mathematical writing for the transmission of pure and simple information, Schulz’s “zero-sum equation.” The second is the furtive use of semantic stitching techniques, replacing periods with commas, semicolons, or interspersed dashes, in order to prevent the isolation of sentences so that their meaning cannot be modified — techniques of media training. The third would be simply not to touch on sensitive topics. The use of these three solutions results in pasteurizing writing to the point that it becomes a barren plain, an aseptic writing that leads to stagnation and the death of communication, potentially even in the form of self-censorship. In them, the outcome is a mortal desert from the absence of the desire to address relevant themes, or Schulz’s “desert of absolute exactitude of language.” In both deserts — of absolute exactitude or of aseptic relief — we lose the rich ambiguity necessary to convey sensations and emotions; we flirt with the weakness of body and soul and the approach of death, as faced in the desert by the fugitives: “we were all perilously weak and dangerously near death.”

The crossing of Tibet’s rugged territory was populated with encounters with a different culture, with varied types of reception, from the friendliest to suspicious and indifferent. Food and places of rest were offered during the journey, keeping the flame of hope alive. In the peaks of the Himalayas, the narrow passes, the snow-covered summits, and the rarefied air changed the face of the challenge; yet they still found refuge in Tibetan monasteries, where monks offered them food, shelter, and blessings. Even without sharing the language, mutual help pushed them forward. Reaching India was the moment of maximum relief, and as the feeling of security grew, the certainty of achieving freedom seemed surreal, marking the end of the physical journey.

The courage to overcome the vastness of geographical variability was the key piece of this journey to freedom; geographical variability was not an obstacle but the path to freedom. What makes our planet — and writing — wonderful is variability, not uniformity. We cannot create uninhabitable deserts out of self-censorship out of fear; we must incorporate the reliefs into our writing. We must write with courage, accepting that negative reactions are the price of relevance, for the art of communication is that which truly mirrors and transforms.

Given that writing is a “flawed act”, the physician-writer must seek refinement, echoing the idea that total communication is a mirage, but continuous attempts can polish the surface, making it more reflective. Perhaps the “perfect physician-writer” is the one who exposes flaws without pretending to resolve them, inviting us to an imperfect, reflective, honest, non-doctrinaire communion. Perhaps true perfection lies in accepting this flaw as a source of beauty, encouraging us to write not for perfection but for imperfect, human connection.

Exposure is inherent to ethical transparency. Transparent writing can mitigate risks by being balanced, pointing out flaws, and proposing solutions. The catalyst is the transposition, the humanization of data — anchored in scientific evidence, protocols, and professional ethics — using concrete tools to accomplish it: metaphors, narratives, literature.

It is not about diluting facts in sentimentalism, but about polishing the language until it, like a frozen river or a desert crossed, can reflect the reader in a transformative way: cold data gain life through stories, empathy, and human context. This mitigates dangers, fostering dialogue rather than confrontation.

Rawicz’s crossing was of life or death; ours, infinitely smaller, but still necessary. Danger, then, is not a barrier, but a catalyst — a reminder that medical writing, like all art, is “quite useless” if harmless, but vital if provocative. The Long Walk embodies this transcendental realization: freedom is not an easy destination, but a conquest forged in varied suffering.

This essay was originally published in Portuguese on August 23, 2025. You can read the original version here: